CBN HOF Series: Ex-Expo GM Dan Duquette on Larry Walker

Larry Walker (Maple Ridge, B.C.) will be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on Wednesday.

His home province of British Columbia is sure proud of him, and so are baseball fans all across Canada. To celebrate Maple Ridge, B.C., native Larry Walker becoming the first Canadian position player to be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, we will be running a series of tribute articles from many who have known and been inspired by him - including former teammates, managers, coaches and even his dad - leading up to the September 8 ceremony. We will also be publishing tributes to Walker's fellow 2020 inductees Derek Jeter, Ted Simmons and Marvin Miller.

***

Steve Rogers on Marvin Miller ||||| Mario Ziino on Ted Simmons ||||| Buck Showalter on Derek Jeter ||||| “The Legend” Dick Groch signed Jeter, plus scouting report ||||| Captain Jeter was Mr. November

***

Larry Walker’s on Larry Walker, Jr. ||||| Clint Hurdle on Larry Walker IIIII Stubby Clapp on Larry Walker IIIII Gene Glynn on Larry Walker IIIII Allan Simpson on Larry Walker IIIII Coquitlam coach Don Archer on Walker ||||| HOFer La Russa on HOFer Walker IIIII Neil Munro on Larry Walker ||||| Kevin Glew on Walker ||||

***

September 6, 2021

The Legend of Larry Walker Junior

By Dan Duquette

Former Montreal Expos GM

The legend of Larry Walker Junior began in the early 1980s when he emerged from the woods of Western Canada, like a lumberjack, wildly swinging an axe to clear trees in the forest.

Fortunately, he caught the attention of Montreal Expos scouts using a wooden bat to hit home runs; at that time lesser men chose aluminum. Having played few organized youth baseball games, Larry learned basic skills playing softball on a team organized by his mom, Mary, to include his dad, Larry Sr., and brothers Barry, Carey, and Gary; Larry was the youngest. He played around 15 games total before playing 70 games one year with the Coquitlam Reds and was discovered representing Canada in a 1984 World Youth Tournament in Kindersley, Sask.

Like most young Canadian boys, he aspired to be a hockey player and faced off against future Boston Bruins great Cam Neely in street hockey. Larry was a goalie, and it would be easy to cast him for Hockey Night in Canada as he was built like the last two championship Montreal Canadiens goalies Ken Dryden and his contemporary Patrick Roy. At 6-foot-3 and 215 pounds. or, 190 CM 97.52 KG which is 15 Stone and 4 lbs. (Whichever you prefer), Larry was long, lean, quick, athletic, strong like Paul Bunyan, smart and fearless. All desirable traits to be a goalie.

He was also a bit goofy (remember when his former Expo teammate Randy Johnson threw behind him at the 1997 All-Star Game and Larry turned his helmet ear flap around and stood in the right-handed batter’s box?). While hockey may have been number 1 in his heart, it was the Expos who called him with a job as veteran scout Bill McKenzie recommended Larry to front office executive Jim Fanning who authorized area scout Bob Rogers to visit Larry in Vancouver to offer a bonus of $1,500 US (“it’s more in Canadian $”) to begin his career.

Thankfully, it was enough to entice Larry to sign because it was just barely enough for a round-trip ticket from Vancouver to the club’s training site in West Palm Beach, Fla. When I first joined the Expos in October 1987, Larry was rehabilitating his knee from an injury he sustained playing winter ball in Mexico. Closer scrutiny of Larry’s experience with Montreal revealed that after signing with the club he was “farmed out” of the organization, his contract assigned on loan to a cooperative team in Utica N.Y. in the New York Penn League for the summer season of 1985 instead of being assigned to the Expos wholly owned Jamestown affiliate in the same league.

Larry was “farmed out” again in 1986 this time to Burlington, Iowa, the arm pit of the Midwest League, rather than being advanced to the Expos’ affiliate in West Palm Beach in the Florida State League. Being sent to a co-op team rather than playing for a club’s dedicated team like Jamestown or West Palm Beach is akin to being placed in a halfway house before being assigned to an authentic work site. Said Larry, “I had lots of learning to do as I was way behind.”

Walker was assigned to other teams while the club was trying to figure out if he was going to learn how to play after limited amateur experience. Despite field reports that he was a wild swinger at the plate and could not recognize spin on the ball due to his lack of at bats, in short order, Larry proved his tools could play anywhere. At the end of the 1986 season, he was recognized as a top prospect for the Expos who at the time had one of elite player development operations. Larry quickly became the poster child of an Expos farm system which produced over 60 major leaguers in nine years leading up to Montreal’s best 74 win and 40 loss season in 1994.

Club curriculum was built on the premise of encouraging players to do what the great Oriole GM and manager Paul Richards taught: “In any given situation, try to be a ‘ball player.’” Being a ball player HOF Manager Leo Durocher wrote in the introduction to Richards’ book, “Modern Baseball Strategy”, which was taught annually in seminars to Expos player development staff, “implies a full understanding of the game and a grasp of its playing principles. The player owes it to himself and his team to acquire this knowledge.”

Richards expounded on this point, “Too few young players study their game like an ambitious young advertising executive, for example studies his trade. Baseball stardom virtually demands such study.” Indeed, after starting behind the 8 ball, Larry Walker showed he was a quick study to “be a ball player.” He was not an “Accidental Ball Player” as Sports Illustrated suggested in an article they published as Walker refined his skills on the diamond and gained popularity.

While he may have been an unlikely ball player given where he was from, what he aspired to as a boy and lack of playing experience, he was gifted with all the physical tools albeit raw, including instincts for the game. Larry also had an unrelenting drive to “be a ball player.” Truly, there are no accidental Hall of Fame players.

I recall Larry’s Montreal manager Felipe Alou saying, “Walker has the tools to be considered for MVP ... every year.” He reminded me of Milwaukee Brewers Hall of Famer Robin Yount, who like Larry had a carefree attitude, free flowing hair, and a burgeoning tool set. As Larry’s Rockies manager former Oriole Rookie of the Year Don Baylor said, “Larry Walker is a six-tool guy.”

Not only could he hit, run, throw, field and hit with power, he had another tool, what the Oriole farm system that nurtured Baylor called the lower half, all the skills that you could not see from a ball player unless you carefully watched him play. Simply, Larry had all the intangibles to be a great player. Watching him play was like looking under the hood of a Ferrari to see the engine that powers the car. Walker had instincts, feel for the game, baseball acumen, know how to adjust in his own game, self-knowledge to adjust to pitchers on any given day, what adjustments he needed to make pitch to pitch, at bat to at bat.

Things like where and how to position in the field to cut off gappers and make throws to cut down opposing base runners. He learned when to steal a base to help his team win a game, had a knack for knowing when to take an extra base and intimate knowledge of the pitchers’ deliveries to the plate and catcher’s release times required to steal a base a high percentage of time. Of those last points I’m sure as Larry learned from Expos instructor Tommy Harper who was a 30 homers/30 stolen base man for the Cincinnati Reds in 1970. In addition to and at the behest of Expos Chairman Emeritus John McHale, we also employed Hall of Famer Lou Brock in 1992 and 1993 to work with him.

Would you like proof that Larry learned to be a ball player and could do it better than just about anyone else? If you take into account advanced metrics, he is one of only three players in major league history to rank within the top 100 of batting runs, base running runs and defensive runs saved. The others are Willie Mays and Barry Bonds. Walker’s 1997 work when he was named Most Valuable Player of the National League was the pinnacle of his skills as he accrued 9.8 WAR, hit 49 homers, and became the only player in big-league history to steal 30 bases the same year he slugged over .700.

Another defining trait which adds to Larry Walker Junior’s legend was the judgments he made to deal with nagging injuries, the ones we all face with age. “The mental approach was mostly something I figured out on my own,” said Larry whose intuitive choices kept him at the top of his game.

Larry’s manager and hitting coach in Colorado, Clint Hurdle explained: “One of the most amazing things I’ve seen Larry accomplish, was during those two seasons after 1997, when, hurt as he was, he hit for a high average. He had to take daily inventory of what was going good and come up with a stroke that would work within the parameters of his health ... It was never dramatic -- a layman’s eye would never notice. But he’d raise his hand on the bat or open his stance, just to have a stroke that was pain-free. It was different every night for two years.”

So, Larry Walker Junior did not win the Stanley Cup in goal for the Canadiens this generation, but he did become a real-life baseball Superhero for all-time. Us Canadians can be proud to celebrate Larry Walker Jr. as the one and only every day Canadian player in Cooperstown.

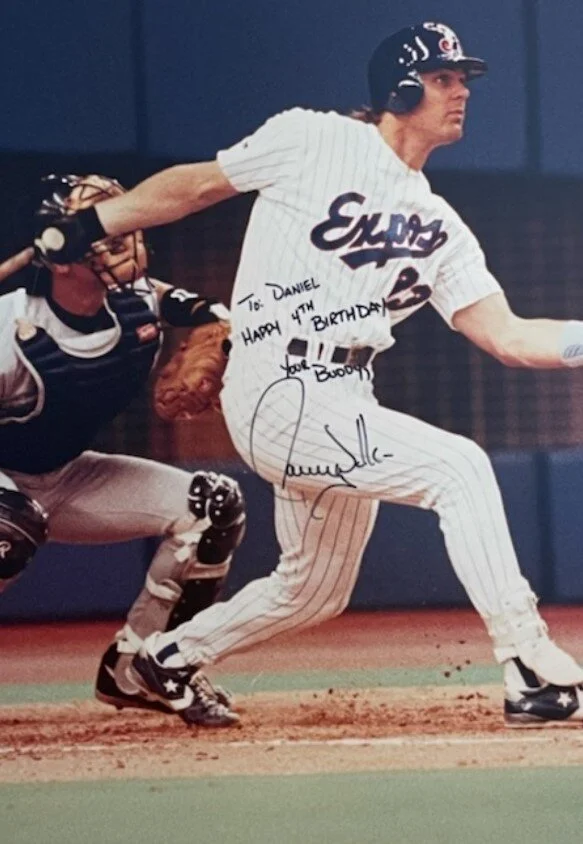

In 1993, my son Daniel, who was born at Royal Victoria hospital in Montreal asked me for an autograph picture of the best Canadian player. I asked Larry to oblige, and he dedicated one of his Expos poster’s writing ...

“Happy 4th Birthday Daniel, your pal Larry Walker.”

The photo that Larry Walker signed for Dan Duquette’s son, Daniel, in 1993.

Fellow Major Leaguer Jeff Francis who also hails from Western Canada appropriately said, ”He lived the ‘unreachable dream’ for kids and let you know it was reachable, that a Canadian could go do it.”

When asked how he would like people to consider his induction to Cooperstown on Sept. 8, 2021, Larry Jr. said: ”A lot of people say to me ‘I’m a typical Canadian’ which is fine because that means they understand I work for results NOT self-promotion. What is important to me, and my family is that I always work hard and be humble. That’s why I work with the Canadian National Teams.”

Merci beaucoup, Monsieur Larry, for coming out of the woods, swinging the axe, and “trying to be a ball player.” You certainly cleared a trail and carved a beautiful legacy for yourself and baseball in Canada ... EH?

***

After working in the Milwaukee Brewers’ scouting department for seven years, Dan Duquette was hired as the Montreal Expos director of player development in 1987. He helped transform the Expos farm system into one of the best in Major League Baseball. He played a significant role in the club’s decision to draft future stars like Rondell White, Marquis Grissom, Cliff Floyd and Jose Vidro before he was elevated to the club’s general manager’s position in 1991. As GM, he made several astute moves, including signing Vladimir Guerrero as an international free agent and trading for Pedro Martinez.

The Dalton, Mass., native left the Expos in January 1994 to accept the GM position with the Boston Red Sox, a post he held from 1994 to 2002. After his departure from the Red Sox, he founded the the Dan Duquette Sports Academy, a sports training center in Hinsdale, Mass., for children aged 8 to 18.

He returned to the major league ranks in 2011 when he was named general manager of the Baltimore Orioles. With the O’s, he oversaw the 2012 team that advanced to the postseason. It was the O’s first post-season appearance since 1997. Two years later, the O’s captured the American League East with 96 wins. His stay with the O’s lasted through the 2018 season.

Duquette has twice been named the Major League Baseball Executive of the Year by Sporting News (1992 with the Expos and in 2014 with the Orioles).