McFarland: Remembering the ill-fated Canadian Baseball League 20 years later

*This article was initially published on Alberta Dugout Stories on December 21. You can read it here.

December 22, 2023

By Joe McFarland

Alberta Dugout Stories

When you have Hall of Fame pitcher Fergie Jenkins as the commissioner and several former MLB players as managers, it wasn’t hard to see why some believed the Canadian Baseball League was the real deal.

With teams in Victoria, Kelowna, Calgary, Saskatoon, London, Niagara, Trois-Rivieres and Montreal, the league positioned itself as the start of a professional baseball powerhouse heading into its inaugural 2003 season.

“The game we’re going to deliver is going to far exceed anybody’s expectations,” said CBL founder Tony Riviera in late-2002. “People are going to be completely blown away.”

However, just midway through their maiden voyage, the tide had completely changed and the league was heavily underwater, leading to its demise.

Sitting with a debt over a million dollars, the league was plagued with issues ranging from a poor business plan and ineffective marketing to poor weather in the east and a lack of fan support in almost every market.

“This business in its current form is not on track to be successful,” said league CEO and principal investor Jeff Mallet. “It’s like trying to change a fan belt with the engine running – we’re going to turn off the engine and fix what needs fixing.”

With the benefit of hindsight, it was clear to see that the league, from nearly the beginning, was set to ride rough waters.

SHORT ON DETAILS

The first few lines of the main story in newspapers on September 27, 2001 served as a warning when the Canadian Baseball League (CBL) was officially unveiled.

“There was a lot of enthusiasm but few hard facts,” read the first sentence in the Canadian Press article that summed up the league’s initial news conference.

With Jenkins at the helm the league was hoping to serve a level of baseball mirroring double-A, with aspirations to give Canadian players in particular some exposure at the professional level.

“We’re going to have a draft, we’re going to bring youngsters in, some college coaches,” Jenkins said. “We’re going to work with these youngsters and expose them to a good brand of baseball.”

While the intentions seemed sincere, reporters were quick to ask questions about the business model, who was backing the venture, or what markets the league was targeting.

Riviera would only say that “private investors that are extremely wealthy” were on-board, and that there had been 25 cities identified as potential franchise locations.

Over the next few weeks, he met with municipal leaders across the country in hopes of finding eight or more suitors.

Despite lingering doubts about financial backing as well as a shaky economy, the league pressed on with its franchise announcement on November 8, 2001.

Abbotsford, Nanaimo, Kamloops, and Kelowna would make up the Pacific Division while Red Deer, Lethbridge, Regina and Saskatoon were part of the Central Division.

“This has been a long process for us as it’s been about four years in the making,” said Riviera. “Our plan is to add an Eastern Division next year of another four teams.”

“Ultimately, we’d like to have three divisions of six teams.”

Just one day after the announcement, another sign emerged that not everything was going to go as planned.

In central Alberta, Riviera had hoped to move a team into Great Chief Park, but the City of Red Deer said it couldn’t commit immediately as it needed to contact residents and amateur teams who used the facility.

So the hope turned to purchasing land in Red Deer County and building a 3,000-seat stadium.

“Red Deer had their chance but they couldn’t make decisions,” Riviera told the Red Deer Advocate.

“We couldn’t sit and wait so we decided to go another route. We’ll build in the county and Red Deer will lose the identity and the economic impact this team will bring.”

Meanwhile, fans in Saskatchewan were also hesitant to buy into the hype.

Having seen many bridges burned during the short-lived Prairie League of Professional Baseball (1993-1997), former founder and president Dave Ferguson sounded the alarm about some of the expectations around the length of the season (72 games), ticket sales and revenues the CBL was projecting.

“I wish them luck, but the way they’re doing it, I don’t think it will be workable,” he told the Regina Leader-Post on November 9.

Former Moose Jaw Diamond Dogs owner Murray Brace agreed, going further by saying after baseball with three different owners and failed attempts at other professional sports, fans had seen this song and dance before.

“Surely the people of Saskatoon and Regina aren’t that stupid,” he said. “They’re trusting and honest people out there, but they’re not stupid – they didn’t fall off the turnip truck on Tuesday.”

Despite the challenges, the league forged ahead with its inaugural draft in December, which saw prominent Canadian pitchers Jeff Francis, Adam Loewen and Dustin Molleken selected.

A FAILED FIRST ATTEMPT

The new year started innocently enough with teams getting their official monikers – Red Deer Outlaws, Lethbridge Dust Devils, Saskatoon Yellow Jackets, Regina Storm, Nanaimo Navigators, Abbotsford Saints, Kelowna Heat and Kamloops Critters.

All wasn’t well in Alberta though, where Lethbridge general manager Les McTavish resigned in early-February.

“I can’t tell you much right now but basically, things just weren’t getting done,” he told the Canadian Press.

“It’s frustrating because we were ready to go, we had everything in place but in the other cities, there was nothing getting done.”

Among those cities was Red Deer, where the dream of building a new stadium in the hamlet of Springbrook – 11 kilometres southwest of the city – became more unrealistic with each passing, wintery day.

General manager Perry Osberg was forced to go back to Red Deer city council, hoping to utilize Great Chief Park for the coming summer, but the city wasn’t able to make it work with the other teams needing the facility.

Shortly after McTavish resigned, Osberg did the same.

“There is a group of us in the country who have spent a lot of time in an effort to get the various teams going and need to know what’s going on,” he told the Advocate ahead of a trip to Vancouver to meet with league officials.

“So far, it’s been a lot of smoke and mirrors and it’s been frustrating.”

Just a week after the resignations, it was announced that plans for the season had been shelved over difficulties with scheduling and getting leases for facilities.

“Maybe we were a little over-expectant, naïve perhaps that we could get it done,” CBL director of communications Alex Klenman said.

“At this time, it’s pretty clear we can’t get it done for 2002.”

League officials turned their attention to fielding a pair of barnstorming teams that would travel the country, building interest in the product.

That idea was quietly nixed, replaced by a handful of September tryouts ahead of an official announcement about the 2003 season.

On November 20, 2002, the Canadian Baseball League declared it was back, albeit with several new teams.

Canadian Press reporter Shi Davidi said that “in a flashy launch long on style and, at times, short on substance,” an eight-team circuit would span the country with four teams in the West and four in the East, all owned by the league.

Once again long on questions and short on answers, they would now have to negotiate ballpark schedules, get players, build fan interest, hire managers, get a TV deal and land sponsors.

All in six months.

“We’re going to be very competitive, and we think we’re going to deliver a profit,” said Riviera during the news conference.

“No war is ever won without a plan and no war ever goes according to plan, so our emphasis and priority right now is to deliver baseball, and do it with the right attitude.”

‘A SKEPTIC’S SMORGASBORD’

With former big-leaguers like Jody Davis in Calgary, Ron LeFlore in Saskatoon and Willie Wilson in London, the Canadian Baseball League was hoping to deflect any questions about the business side of their operations with the quality of people running the teams.

They got an added boost when they signed a deal with The Score television network to broadcast 18 of their games, along with the All-Star Game in Calgary, and the best-of-seven Jenkins Cup championship.

Yet again, the league faced another major hurdle in one market: Montreal.

Heading into February, Riviera said the league still didn’t have a home-opener date for the Royales, and were looking into converting Claude Robillard Centre, the outdoor home of the Montreal Impact soccer team, into an 8,000-seat baseball facility.

As John Lott wrote in the February 22 edition of the National Post newspaper, “three months from launch, the CBL remains a skeptics’ smorgasbord with eight teams, five stadium leases, four confirmed managers, mostly anonymous players and two schedules, just in case the Royales would have to play all of their games on the road.

Riviera was also trying to hem together last-minute deals on facilities, including Saskatoon, where questions lingered about the future of the Western Major Baseball League’s Saskatoon Yellow Jackets.

Interestingly, he told a Saskatoon Star-Phoenix reporter that a deal was done, while the man handling the local negotiations seemed in the dark about it.

“I haven’t talked to them yet,” Geoff Hughes said with what was described as a “long, shocked laugh.”

Even later in the evening of Feb. 27, Hughes still didn’t agree that things were final, adding there was at least one minor point needing to be settled.

When it came to the Yellow Jackets, Riviera shot back with what had become a trademark tone when faced with questions about his aspirations.

“I find it an insult that the Yellow Jackets are crying we’re not supporting them, and this and that,” he said. “I find it pretty interesting that we purchased 200 tickets for underprivileged kids last year to go to Saskatoon Yellow Jackets games – we’ve done nothing but support them.”

Meanwhile, Riviera was also involved in another major storyline as he had nominated Pete Rose to be inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame because of his late-career cameo with the Montreal Expos.

While it got major press south of the border, shining a light on the inaugural CBL season, it didn’t seem to quell the concerns being felt in the markets set to host Opening Day events in just a few short months.

INTO THE GREAT UNKNOWN

As the weeks progressed, things seemed to settle down for the fledgling league.

Schedules were announced (although Montreal would be on the road all year after not getting a lease in place), player signings started rolling in, and another major financial backer came in the name of former Yahoo president Jeff Mallett.

“I read an article in the Sports Business Journal, which gave the league a pretty good positioning, and I literally that moment looked up the phone number and called and said this is who I am and can we talk?” he told the National Post.

The league, who signed all of the players, then held a dispersal draft to provide teams with their players. However, the results were kept out of the news for a few days.

Each team was provided with 18 players, while additional tryouts were held to fill out the rosters. Some squads voiced some concern over the small size of their teams and the prospects of only having eight or nine pitchers on their staffs.

By early-May, each team was getting set with training camps, including the Calgary Outlaws, who faced a similar fate to that of the Calgary Cannons nearly two decades earlier when a blizzard forced everyone inside.

“That’s baseball, I guess … I could never figure out why you’d go to Arizona for six-seven weeks and then you’d open the season in New York or Montreal or Chicago,” said manager and former MLB catcher Jody Davis.

“Can’t we play in Atlanta, San Diego or Houston instead? I could never understand that. It’s no fun to play in that kind of weather.”

Despite all of the pre-season challenges and questions about the league, the players were excited to showcase their skills and put Canada on the professional baseball map.

“To be honest, I’m not too sure yet,” former MLB pitcher Steve Sinclair told the National Post ahead of his debut with his hometown Victoria Capitals. “I think it’s going to be a decent calibre of baseball.”

Others were hopeful about the opportunity to get into the community and build the brands of their respective teams.

“That’s how you’re going to make a franchise work, by getting in the community,” said Niagara Stars outfielder and fellow former big-leaguer Rob Butler.

“On the field, you want fan favourites, that brings the fans in.”

While first pitch hadn’t even been thrown yet, league officials were once again talking about expansion and profits.

“We can become profitable in the first year,” stated league co-founder and former Microsoft executive Charlton Lui to The Canadian Press.

“If we’re not, we’re fine, we can do this for several years knowing we can fund this.”

He believed the league could expand to as many as 18 teams across three divisions in the not-too-distant future.

ALL THE RIGHT THINGS

On May 21, first pitch was finally thrown by the new Canadian Baseball League, as Montreal opened the season in London.

In an effort to speed up the game, the league introduced rules such as forcing batters to stay in the box between pitches, and sending designated runners in for catchers with two out in an inning.

The most fan-friendly policy may have been the introduction of a cheaper can of beer at Burns Stadium in Calgary.

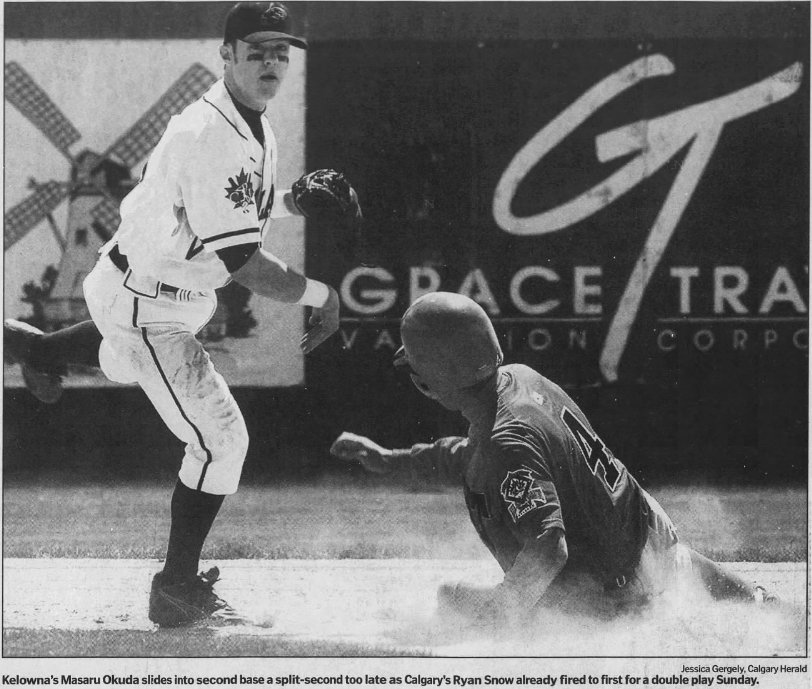

“Cash-scorched spectators sick of forking out $6 for a watered-down, flavourless draught should find some solace in the $3.75 can – yes, can – of Sleeman at Burns Stadium,” wrote the Calgary Herald, ahead of the opener for the Outlaws against the Kelowna Heat on May 22.

The team was also offering hot dogs for $2.25 each, in an effort to show fans an affordable time.

“I think the pricing is fair to our bottom line, and fair to the fans,” said general manager Glenn Dmetrichuk.

“If we can show that a family of four can come to a game for $40 and get a program, hot dog and drinks, we’ll get them back numerous times.”

He was also hoping the quality of play would make people forget about the Pacific Coast League’s Calgary Cannons, who were relocated after the 2002 season.

Nearly 2,000 fans were in attendance for the affair, described as a wild, back-and-forth game which ended with a 7-6 home team loss. The game included a few miscues, including the exclusion of “O Canada” due to technical difficulties.

Jenkins was also in attendance to throw out the ceremonial first pitch and also sang “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” during the seventh inning stretch.

He was asked about the challenges facing the league, with the most notable being the public skepticism about the calibre of players.

“I’m doing this because I think it will work and if it doesn’t, in three years I’m out of here,” said the Canadian great. “I’ll go back to the ranch.”

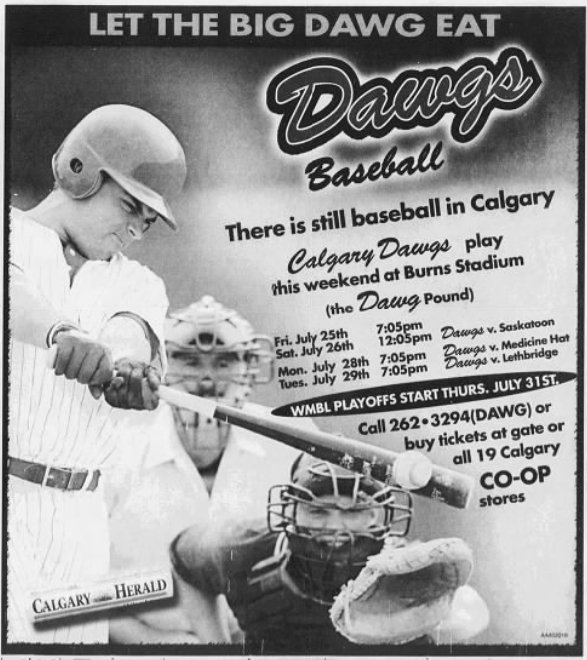

IN THE DAWG POUND

The summer of 2003 also ushered in another chapter for baseball in the Calgary region.

The Western Major Baseball League’s Calgary Dawgs launched on May 30 against the Lethbridge Bulls, giving fans options.

Team officials said they were confident about the franchise, adding they faced no issues with scheduling conflicts at Burns Stadium, and they weren’t concerned about splitting the fan base.

“If there’s 20 people or 2,000 or 10,000, we’re just excited,” said Dawgs president William Gardner.

“We’re not really reliant on a huge turnout to meet numbers or projections.”

Meantime, the CBL season continued on with positive news coming in the form of a partnership agreement with Baseball Canada to field a national team for the World Cup qualifier.

The league announced plans for an All-Star Game weekend in Calgary for the weekend of July 22-23, including two home run derbies and an autograph session.

However, the tune started to change in Calgary after Canada Day as the agreement between the Outlaws and Dawgs had turned sour.

“I’m not going to get into airing our differences in public,” Gardner told scribe George Johnson in the July 14 edition of the Calgary Herald.

“Let’s just say it would’ve been better if we’d both done more to work together this year.”

He said baseball fans were pleasantly surprised by the quality of baseball they were seeing out of the first-year summer collegiate franchise, and that it would be up to the owners of the stadium – the City of Calgary – to determine who would be the primary tenant in 2004.

“I think we’re over the confusion about who we are and who others are,” Gardner continued. “I see growth in the future, whether that means going from 600 a game to 800 or beyond next year.”

OVER BEFORE IT STARTED

Less than a week later, the Canadian Baseball League dropped a bombshell by announcing it would suspend its season after its All-Star Game.

Refusing to say that the league was folding, CBL chairman Jeff Mallett said it needed a timeout to look at the problems with the business plan with the hope of bringing the league back stronger in 2004.

Attendance had become the biggest barrier, with crowds as small as 50 taking in games in London. The Niagara Stars, Trois-Rivieres Saints and Montreal Royales all struggled.

While Calgary, Kelowna and Victoria were able to scratch together decent crowds, Saskatoon was said to be “hit-and-miss.”

“Disinterest in the league and a messy on-field product also prompted cable TV’s The Score to pull the plug on its weekly broadcasts,” Davidi wrote.

“The CBL never made the in-roads into local communities it needed to and the on-field product was a little rougher than most people expected.”

The decision came with disbelief from players, including Outlaws pitcher Zach Murray.

“I’d heard rumours that there were financial difficulties and differences of opinion at the top, but to have them actually close it down is pretty drastic,” he said.

“Knowing what I know now, the business end wasn’t up, but it still kind of leaves me here in an awkward position.”

Murray and his teammates were technically under contract until the first part of August, so they agreed to stick around until the last homestand to see if they could capture the CBL championship.

However, that wasn’t going to stop them from calling contacts in the Frontier and Pioneer leagues, hoping to find a baseball home for the final month or two of the summer.

LAID TO REST

Once the final regular season game was played, the Outlaws were crowned the champion of the Canadian Baseball League with a 24-13 record.

All that remained was the All-Star Game, with the East and West battling to a 5-5 tie through 10 innings before the West emerged with the victory thanks to a tie-breaking home run derby.

An announced crowd of 5,700 came through the turnstiles, which ended up being one of the best turnouts of the season.

“I guess Calgarians would rather come to a funeral than a wedding,” chimed Dmetrichuk.

It was later confirmed that the CBL was going into receivership with a reported $1.7 million owing to 339 creditors.

While the Outlaws were out of the picture, the Dawgs ended up facing further challenges with their Burns Stadium cohabitants, starting with talks of a professional soccer team later that year, followed by the Calgary Vipers entering the Northern League in 2005.

Ultimately, the summer collegiate squad would move to Okotoks, becoming the crown jewel of what is now the Western Canadian Baseball League.

As for the Canadian Baseball League, Jenkins believed even years later that the idea wasn’t that far-fetched.

“It’s unfortunate – I still feel it could have worked out,” he said in a 2008 interview. “What happened is that we ran into some terrible early-season weather, especially in Eastern Canada. I thought we had a good product.”

While the idea may have had merit, the execution left a lot to be desired. And as a result, 20 years later, you can’t blame baseball fans for having a short memory of a half-season of the Canadian Baseball League.