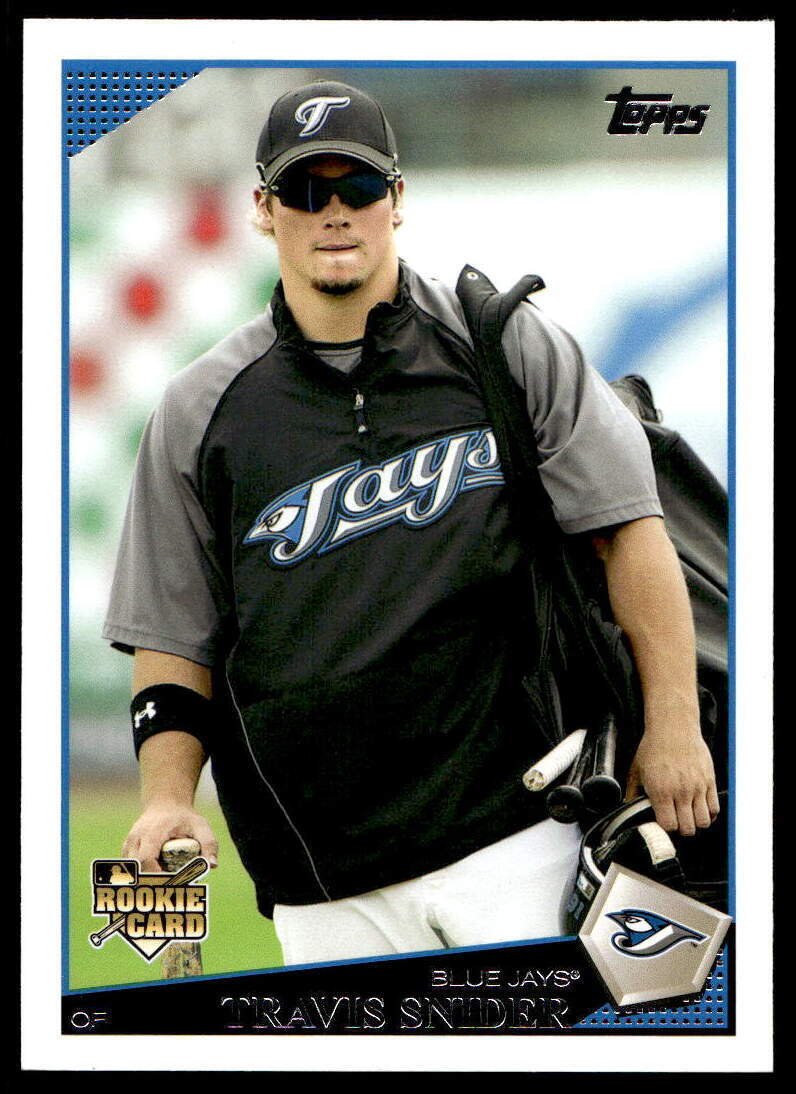

Retired ex-Jay Snider hopes to help other players with mental aspects of the game

Former Toronto Blue Jays outfielder Travis Snider, who officially retired in January 2022, is hoping to help other players with the mental aspects of baseball in the next phase of his life.

March 15, 2023

By Melissa Verge

Canadian Baseball Network

If you build it, they will come. And come they do.

It doesn’t matter that it's a sticky day in August 2009 that feels like 40°C.

There’s 25,472 of them willing to risk sweaty legs that may never come unstuck from blue stadium chairs for a ball game.

Some are diehard for the Blue Jays, others are diehard for the ballpark beer and will wobble out after the seventh inning last call. Party A knows the players stats by heart, and that a young Travis Snider will be returning to the team after a stint in triple-A. Party B will go to sleep and forget all about the score after consuming one too many cold ones.

It’s both parties though, who mill around the Rogers Center concourse, oblivious to the 21-year-old Snider down on the field who feels like he doesn't belong.

He has all the skills. The top prospect title is one of the high expectations that have followed the young athlete like spring follows winter. But beneath the Jays cap, there’s a case of imposter syndrome going on in Snider’s head.

“Do I really belong here? Am I really this good?” Those two thoughts keep repeating for the young athlete, which fans - even from the first row seats in the 100 level - can’t see.

That mental struggle continued for Snider throughout his career, something the now 35-year-old has had a chance to reflect on in the just over a year since he retired.

The fear that followed him after initially being sent down and returning to Toronto in that August game many years ago never went away.

He was always worried, looking over his shoulder when he saw the bench coach. His impressive skills on the diamond were moot, overshadowed by the fear and anxiety that followed him daily.

“It's not like I didn't know how to hit a baseball, but I realized how much the mind and the analysis, and the paralysis from analysis can be the driving factor,” he said.

The mental aspect of the game is something he’s learned from and thought a lot about in retirement. His tumultuous career hasn’t turned him off the sport - although he doesn’t “have the itch to field fly balls.” He now hopes that through his experiences he can help athletes better manage the pressures and expectations, the love and the hate which come with being a high caliber athlete. He also wants to help provide them with resources so that they can get support they need in different ways.

As a player he had a lot of help from mental skills coaches within the organizations he was with. Back then, there was more of a stigma around accessing treatment. Veteran guys in the clubhouse would make a joke about the head doctors here, who’s banged up, kinda thing, Snider said, who was pretty open to working with them.

He had a lot of help from inside support, but outside mental health support is also important for players to access. It can be a difficult balance as an athlete judged on performance to confide in teams. The more information a club has the more they can help, but it could also be used against players when it comes time to make a decision, he said.

“That’s an area that I’m interested in, being able to work with guys, whether it be with one organization or multiple organizations, in a space where I can help them kind of navigate through the ups and downs that we're talking about, this rollercoaster of this journey of being a baseball player.”

During his playing days his identity was so closely tied to his work performance. It’s a common and relatable feeling for non-professional athletes, but in the public eye, if Snider did or did not perform it was on a whole different scale. If he did, there was love that poured out, seen in the 20 reporters who loitered by his locker on his MLB debut, or the newspaper article he still remembers from his freshman year in high school titled “You don’t know Travis…yet.” It was evident in the fans screaming his name from the 200 level outfield at the Rogers Centre. If he didn’t perform, there was hate from social media, and it was all analyzed just as closely in newspaper articles, by fans at the game and on his 50,000 social media following.

That low was rough, he said, and the energy and high were impossible not to chase.

“No matter how hard we try the identity of being in whatever sport you play [for me] professional baseball player, there's an amount of love you that you look and you seek to receive from playing that sport,” he said.

Hundreds of hours of therapy have led him to a place where he feels comfortable enough to have these talks. There’s a darker side to professional sports, and a mental toll grinding it out in triple-A with big dreams and high expectations from fans, coaches, family and yourself can have.

He’s since had an offer in baseball to interview for a hitting coach position, but he turned it down. He’s still very passionate about the sport, but his identity is more than the baseball uniform he put on every year when February rolled around. He gets up between 4:30-5:30 daily, which gives him an hour or two to work on different business ventures before his family wakes up. One of them is a baseball and other sports guide book he’s working on with Seth Taylor, a therapeutic life coach. The idea is to hopefully have it ready and start marketing it in the next three to six months.

Another is a step back to his playing days - a potential podcast down the line where he can share his experiences and struggles, featuring former teammates and friends who have also experienced ups and downs at a high level on a huge platform. The goal would be to empower people and better prepare them for life after baseball.

“The most important part of it is what type of human beings are we building, what are they going to be able to do when someone says ‘hey, you're not good enough to play baseball anymore,’ what kind of an impact are they going to have on the world.’”

Business takes up a lot of time, but the most important job he has is as dad and husband. When the roar of the crowd faded, when the uniform was folded, that helped Snider find his identity and peace away from the diamond. So much of his ego and identity were driven by the idea of being a Major League Baseball player. He was filled with the same emotions his non-professional athlete counterparts all experience - the fear of failure, the desire for love and acceptance at the forefront. The highs were magnified times 100, and when the lows came, they also hit just as hard.

“I had to let go of those things,” he said. “And just accept being a 35-year-old man who's married with three kids, who had this incredible experience of playing baseball for better or for worse.”