Remembering Jackie Robinson's season in Montreal

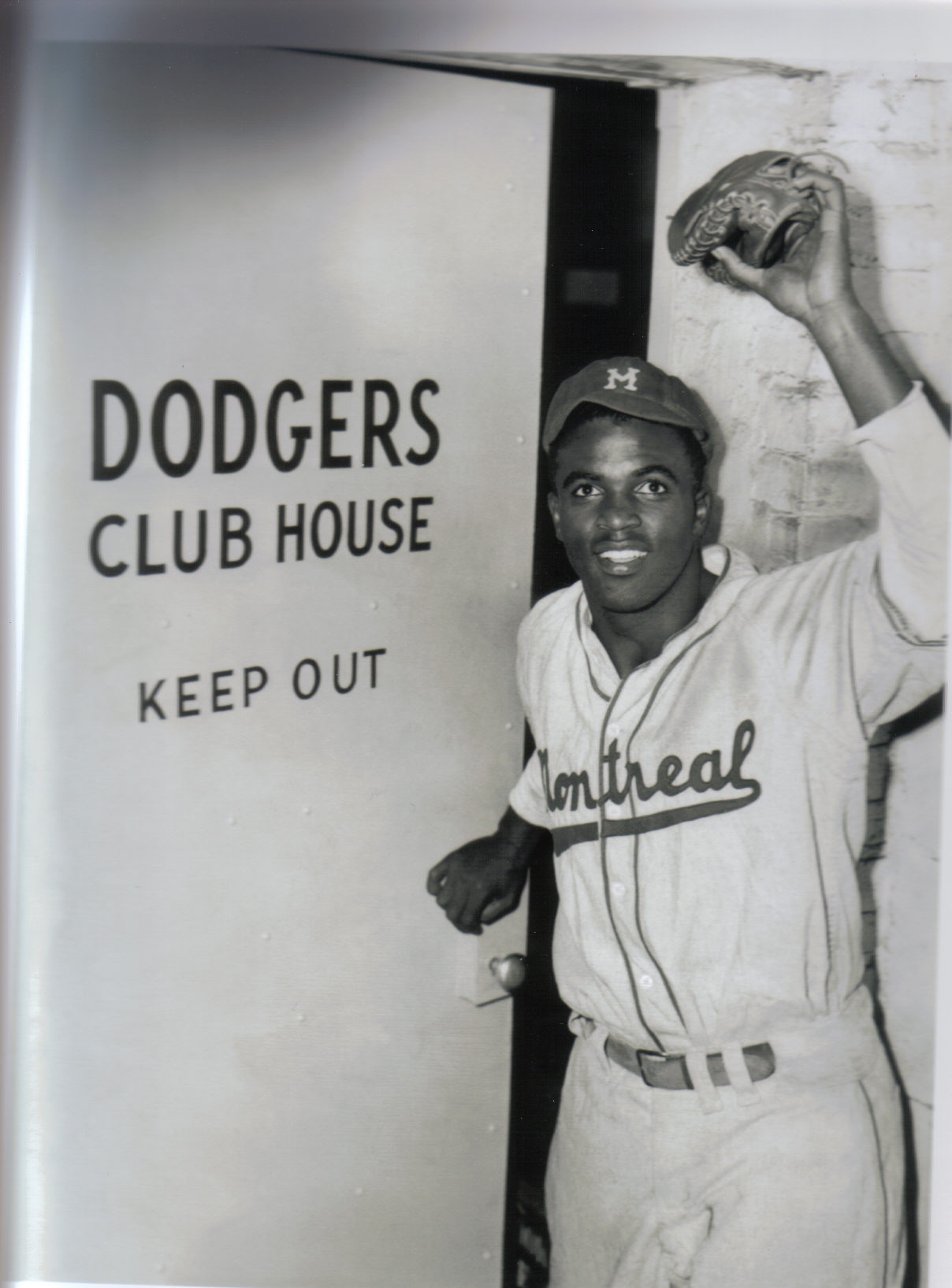

Jackie Robinson played his first season of integrated baseball with the International League’s Montreal Royals in 1946 before breaking Major League Baseball’s colour barrier the following year.

*It’s Jackie Robinson Day in Major League Baseball. Here’s an article that has been published on CBN for the past few years. It has never been more important to remember Jackie Robinson than right now.— Kevin Glew, CBN editor.”

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

How do you do justice to the most important player in baseball history?

That’s the quandary the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in St. Marys, Ont., has faced when sharing Jackie Robinson’s story — especially when space is at a premium in the facility, even with the new renovations.

The answer is you probably can’t.

The Canadian ball hall does a superb job of celebrating Robinson with large photos, but no matter how much room a museum has, it would be impossible to fully illustrate the impact this courageous pioneer had on his sport.

But today, on Jackie Robinson Day across Major League Baseball, and on the 75th anniversary of Robinson breaking MLB’s colour barrier, it’s gratifying to know that we, as Canadians, helped him alter the history of his sport and inspire social change across North America. And Robinson never forgot that.

"I owe more to Canadians than they'll ever know,” Robinson once remarked after his playing days. “In my baseball career they were the first to make me feel my natural self.”

Prior to breaking Major League Baseball’s colour barrier in 1947, Robinson starred at second base for the Montreal Royals, a Brooklyn Dodgers farm team, in 1946. It’s widely believed that Dodgers GM Branch Rickey stationed Robinson in Montreal to ease his young prospect into integrated baseball. Playing his home games in a city with a reputation for racial tolerance would provide Robinson with relative tranquility for half the schedule.

“When I was 16, in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke into the major leagues, and that was the first time most baseball fans had ever heard of him,” wrote Willie Mays in his 1988 autobiography. “But we all knew who Jackie was. In fact, to us black ballplayers it seemed like a bigger breakthrough when, in 1946, he signed to play with the Dodgers’ farm team in Montreal. That was organized ball. I mean, forget about the majors.”

On the field with the Royals in 1946, Robinson excelled, leading the International League in batting average (.349), walks (92) and runs (113), and spurred the club to their first Junior World Series title.

When the Royals clinched the championship at Montreal’s Delorimier Stadium, the fans chanted Robinson’s name and hoisted him on their shoulders. Tears of jubilation spilled from the baseball pioneer’s eyes. He had endured a lot that season. Racism was palpable in International League cities like Syracuse and Baltimore, but the taunts had intensified in Louisville, the city Montreal opposed in the Junior World Series.

After the celebration appeared over, Robinson emerged from the clubhouse, only to have adoring fans chase him down the street, wanting to touch their hero one last time. The scene inspired Pittsburgh Courier correspondent, Sam Maltin, to write, “It was the first time that a white mob chased a black man down the street, not out of hate, but because of love.”

Moved by the affection of Montrealers after the Junior World Series triumph, Robinson remarked, “This is the city for me. This is paradise.” These words have been immortalized on a statue of Robinson that still stands outside of Montreal’s Olympic Stadium.

Jackie Robinson signing autographs for fans during the 1946 season with the Montreal Royals. Photo Credit: Montreal Royals (@Royals_46season) on Twitter

Robinson, of course, went on the enjoy a successful, 10-year big league career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Named the National League Rookie of the Year in 1947, he was voted the league MVP two years later and would be selected to six All-Star games. In all, in 1,382 major league games, he batted .311 and posted a .409 on-base percentage.

For his efforts on and off the field, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. Sadly just 10 years later he passed away from a heart attack when he was only 53.

Robinson and his wife, Rachel, who is now 98, never forgot their year in Montreal. And Montreal and Canada never forgot them.

Robinson was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame posthumously in 1991 and 20 years later a plaque was erected in front of the duplex in Montreal that the Robinsons lived in during the 1946 season.

"When I hear of bad things that are happening in other places – where people are fighting or being violent and are trying to exclude African-Americans – I think back to the days in Montreal," Rachel Robinson told the Globe and Mail in an interview in 2013. "It was almost blissful."